Helping your dentist help you

Human Research Ethics Online Training

I. Introduction

Human Research Ethics Online Training Module for eviDent® Investigators

This module is a modification of the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Online Training Module for the Social Sciences and Humanities, originally written by L.L. Wynn, Paul H. Mason and Kristina Everett and modified by Dr. Denise L. Bailey.

This free educational resource examines the particular ethical issues raised by research involving human participants, with a focus on dental research. The training module is divided into 5 basic parts. You can start and stop reading at any point in the module, and you can close it and return to it later. After you have reviewed the entire module, there is a quiz that tests your comprehension of the material.

It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike license. In other words, others may download, redistribute, remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as they credit the original authors and license their new creations under the identical terms. All derivative work must also be non-commercial in nature. (c) 2008 Creative Commons Some Rights Reserved. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ for more information.

Contents

- History of research ethics violations and regulation

- Basic tenets of ethical research practice

- Ethics Controversies: Case Studies

- Doing research in Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Island communities

- Quiz

What is human research?

It includes any research in which human beings:

- take part in surveys, interviews or focus groups;

- undergo psychological, physiological or medical testing or treatment;

- are observed by researchers;

- researchers have access to their personal documents or other materials;

- the collection and use of body organs, tissues or fluids (e.g. skin, blood, urine, saliva, teeth, hair, bones, tumour and other biopsy specimens) or their exhaled breath;

- access to their information (in individually identifiable, re-identifiable or non-identifiable form) as part of any existing published or unpublished source or database.

Reference: The text above is adapted almost word for word from the Australian National Statement p.8

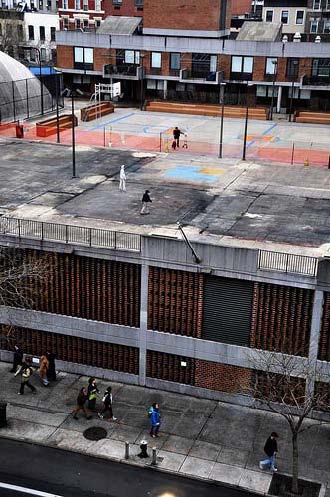

Cartoon by Paul Mason. According to the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (henceforth referred to simply as the "Australian National Statement"), human research is any investigation that is conducted with people, about people, on tissue from people, or using data concerning people.

Cartoon by Paul Mason. According to the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (henceforth referred to simply as the "Australian National Statement"), human research is any investigation that is conducted with people, about people, on tissue from people, or using data concerning people.

What is ethical research?

According to the Australian National Statement,

" 'ethical conduct' is more than simply doing the right thing. It involves acting in the right spirit, out of an abiding respect and concern for one's fellow creatures."

Ethical human research is more than just "ethical 'do's' and 'don'ts' - namely, an ethos that should permeate the way those engaged in human research approach all that they do in their research." [1]

The central values and principles of ethical research include:

- Research merit and integrity

- Justice

- Beneficence

- Respect

[1] National Statement, preamble, p.3

Photo by a member of the Clinical Trials Group at The University of Melbourne

Photo by a member of the Clinical Trials Group at The University of Melbourne

II. A Brief History of Research Ethics Violations and Regulation

Introduction

This section reviews some famous moments in the history of research ethics violations and regulations, from the horrific Nazi experiments that were revealed in the Nuremberg Trials and which led to the development of the first human research ethics codes, to more recent debate about anti-retroviral treatment research in Africa and the United States.

Nazi Human Experimentation

During World War II, the Nazis conducted gruesome experiments on human beings who were prisoners in Nazi concentration camps. [1]

For example, male and female prisoners were injected with painful chemicals or their genitals were exposed to radiation to test methods of human sterilization.

Some prisoners were deliberately burned with chemicals to simulate the effect of bombs, or put in freezing air or ice water for hours at a time, so that treatments for burns and cold exposure could be tested.

Other experiments involved injecting people with gasoline, live viruses, and forcing people to ingest poisons.

Many of the people who were experimented on were killed, maimed, or disfigured by the Nazi experiments. Those who were not killed by the experiments themselves were often subsequently killed in the gas chamber because the injuries from the experiments left them unable to work in the concentration camps.

[1] NIH OER Protecting Human Research Participants, http://phrp.nihtraining.com/users/pdf.php

Operating and autopsy table in the Struthof concentration camp. Experiments were done to find a vaccine for typhus and to find a way to treat burns caused by mustard gas. Photo by Danielle Sainton.

Operating and autopsy table in the Struthof concentration camp. Experiments were done to find a vaccine for typhus and to find a way to treat burns caused by mustard gas. Photo by Danielle Sainton.

The Nuremberg Trials and the Nuremberg Code

In 1946 the atrocities committed by Nazi scientists in the name of research were investigated in War Crimes Tribunal at Nuremberg (often called the "Nuremberg Trials"). 16 doctors and administrators were found guilty of "willing participation in the systematic torture, mutilation, and killing of prisoners in experiments." *

This led to development of the Nuremberg Code in 1947. The Nuremberg Code was the first international code of research ethics. It mandated that research involving human beings must follow 10 basic directives, including:

- voluntary, informed consent from research participants;

- no coercion to participate in research;

- only properly trained scientists should carry out research;

- any risks must be outweighed by the humanitarian benefits of the research;

- research should be designed to minimize risk and suffering

- participants can end the experiment at any time, and researchers must stop the research if it becomes apparent that the outcomes are clearly harmful.

Reference: NIH, Protecting Human Research Participants, p.11-13; http://phrp.nihtraining.com/users/pdf.php

The Nuremberg Trials, looking down on the defendants' dock, circa 1945-1946.source: National Archives Collection of World War II War Crimes Records, 1933 – 1950

The Nuremberg Trials, looking down on the defendants' dock, circa 1945-1946.source: National Archives Collection of World War II War Crimes Records, 1933 – 1950

Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

The infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment proved that the Nuremburg Code wasn't enough to prevent abuse of research participants by medical researchers.

The experiment ran from 1932 to 1972. The research subjects were poor African American men, sharecroppers in Alabama (a southern state in the U.S.). They were coerced by various means to participate in the research. For example, they were told that having painful spinal taps was a "last chance free treatment" for disease, when it was not a treatment at all.

The men in the experiment were told they were being treated for "bad blood." In fact, they were only observed to watch the progression of the disease. The doctors never treated them at all.

Reference: http://www.tuskegee.edu/Global/story.asp?S=1207512

See also: James H. Jones, 1993. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Free Press.

Participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. source: National Archives and Records Administration.

Participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. source: National Archives and Records Administration.

When the experiment started in 1932, there was no complete cure for syphilis, but there were treatment programs that were known to help, involving bismuth, neoarsphenamine, and mercury. But during the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, these treatments were withheld from the participants, or given in doses so small as to be ineffective.

Even when penicillin, a cure for syphilis, was discovered in the 1940s, participants in the Tuskegee syphilis trials were never told or treated. In fact, they were actively prevented from receiving treatment so that doctors could continue to watch the progress of syphilis.

By the end of the trial, "28 of the men had died directly of syphilis, 100 were dead of related complications, 40 of their wives had been infected, and 19 of their children had been born with congenital syphilis."[2] In other words, even though they were not deliberately infected with diseases by researchers, as the Nazi experimenters had done, the fact that researchers deliberately withheld treatment meant that not only did the men in the study suffer for decades, others who were infected by them also suffered and were disfigured by the disease.

[2] http://www.tuskegee.edu/Global/story.asp?S=1207512

Participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment source: National Archives and Records Administration

Participants in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment source: National Archives and Records Administration

There was no scientific benefit from the study. Simply watching how the disease progresses did not help to find a cure for syphilis, and it did not help reduce the spread of venereal disease.

The Tuskegee Syphilis experiment has had a far-reaching impact on much more than just the health of the men involved. The "Legacy of Tuskegee" is that many African-Americans distrust white doctors and the government:

"In 1990, a survey found that 10 percent of African Americans believed that the U.S. government created AIDS as a plot to exterminate blacks, and another 20 percent could not rule out the possibility that this might be true. As preposterous and paranoid as this may sound, at one time the Tuskegee experiment must have seemed equally farfetched.

"Who could imagine the government, all the way up to the Surgeon General of the United States, deliberately allowing a group of its citizens to die from a terrible disease for the sake of an ill-conceived experiment? In light of this and many other shameful episodes in our history, African Americans' widespread mistrust of the government and white society in general should not be a surprise to anyone."[3]

Other Infamous Allegations of Human Research Ethics Violations

There were many other cases of ethically troubling research in the U.S. Two well known examples include:

- In the Willowbrook State School Hepatitis Study (1963-1966), mentally disabled children were deliberately infected with hepatitis so that researchers could test gamma globulin as a treatment. Some parents were coerced into consenting to let their children be infected because they couldn't get their children into the school unless they agreed to let their children be part of the study. The researchers justified the deliberate infection by arguing that children in that school would probably come down with hepatitis anyway, because the disease was chronic in that institution.

- In the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Study (1963), chronically ill patients were deliberately injected with live cancer cells without documenting informed consent. Researchers said that patients had given oral consent, but investigation showed that many patients were in no mental state to give truly informed consent.

- In a much more recent example (1999), the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center was ordered to halt all human experiments when it was alleged that mental patients were deliberately taken off their medicines so that researchers could study their symptoms. [1]

[1] Phillip J Hilts, "VA Hospital Is Told to Halt All Research." New York Times, 25 March 1999.

Visit this website http://phrp.nihtraining.com/history/07_history.php for an interactive timeline outlining important ethical events (developed by the U.S. National Institute of Health).

The Helsinki Declaration

While the Nuremberg Code was an important development in regulating ethical research, it clearly was not enough to prevent tragedies like Tuskegee.

The Helsinki Declaration was another key historical moment in regulating research on human beings. It was developed by the World Medical Association in 1964 in Helsinki, Finland as an elaboration of Nuremburg Code, with a focus on biomedical research.

One of the key differences between the Helsinki Declaration and the Nuremberg Code was that Helsinki allowed for proxy consent from individuals who were unable to give informed consent to research (such as children and the mentally disabled).

Another key development was the 1975 revision of the Helsinki Declaration, which introduced the concept of independent oversight committees to review the ethics of research. In Australia these are "Human Research Ethics Committees" (HRECs).

The Helsinki Declaration has been formally revised 5 times between 1964 and 2000. The most recent revision takes into account debates over differing standards applied to research conducted in wealthy and less developed countries.

The Declaration of Helsinki on the World Medical Association website.

The Declaration of Helsinki on the World Medical Association website.

Helsinki and Controversy Over Art Trials in Africa

The Helsinki Declaration stipulates that no one group of society should disproportionately bear the costs of, or reap the benefits of, research. The Helsinki Declaration also says that any research participant should receive the best treatment available:

"In any medical study, every patient - including those of a control group, if any - should be assured of the best proven diagnostic and therapeutic method.."

It also declares that "the populations in which the research is carried out [must] stand to benefit from the results of the research." [1]

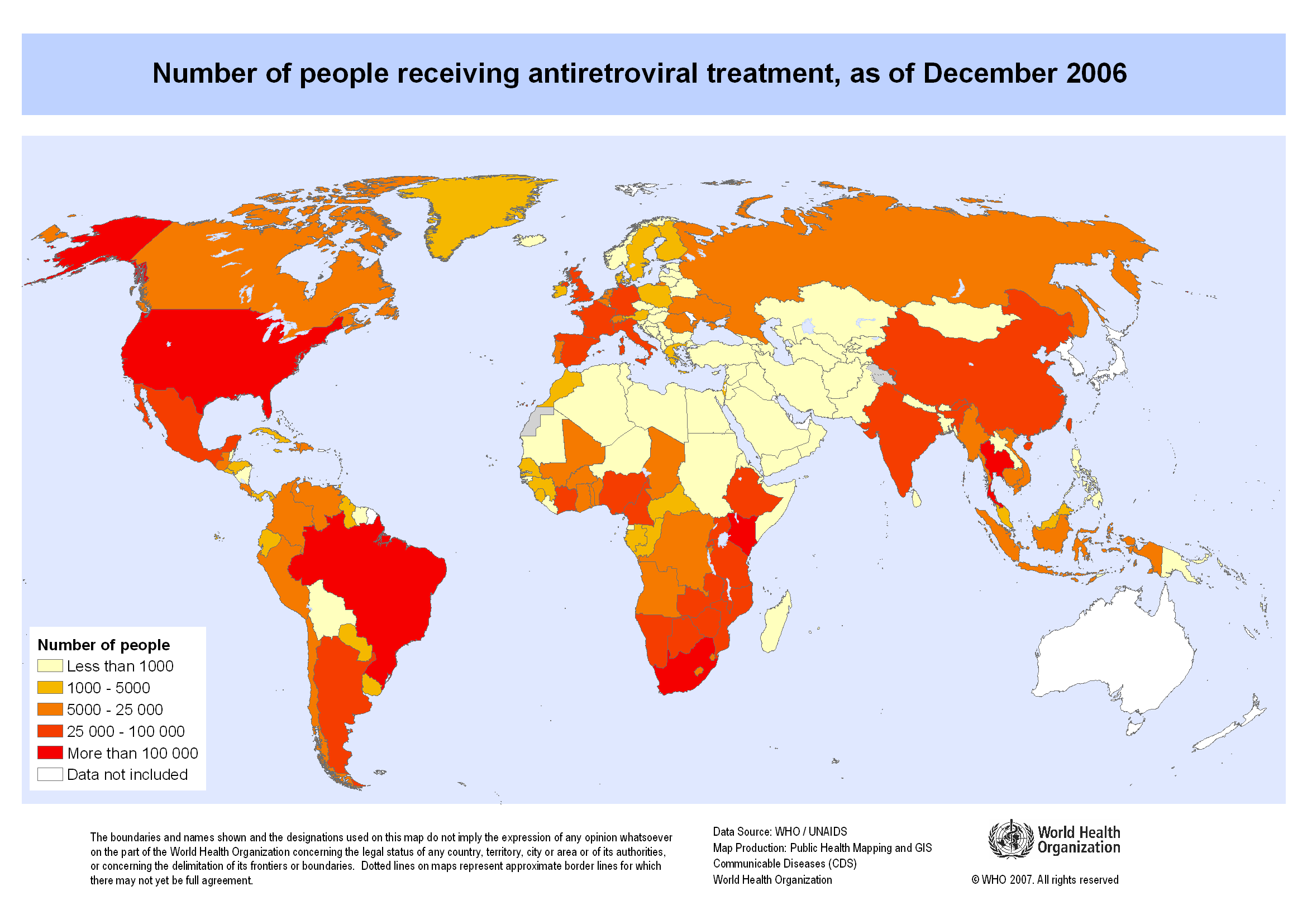

But anti-retroviral therapy (ART) trials in Africa have shown how transnational research poses new challenges to the principles of ethical research. In the wake of the HIV-AIDS epidemic, poor countries have been used to test new drug therapies because medical trials in such countries are much cheaper than medical trials in wealthy, developed countries. But the people participating in medical research in poor countries have not been given the same treatment as patients in wealthy countries. They also have not benefited to the same extent from the development of new drug therapies to treat HIV transmission.

Map showing the number of people receiving antiretroviral therapy as of December 2006. Copyright 2007 World Health Organization, all rights reserved.

Map showing the number of people receiving antiretroviral therapy as of December 2006. Copyright 2007 World Health Organization, all rights reserved.

Controversy Over Art in Africa

Briefly: in the early 1990s, clinical trials were undertaken in several developing countries (mostly in Africa) to test how anti-retroviral therapy could be used to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV. While the clinical trials were underway, a particular treatment regimen (ACTG 076) was found to be effective in reducing mother-to-child transmission of HIV. However, the drug regimen was expensive and required multiple interventions from health care workers.

Because the drug and the health-care costs were so expensive, most of the trials that were studying how to reduce perinatal (mother-to-child) transmission of HIV used a placebo. The justification was that it was too expensive to provide the proper regimen of ACTG 076 in developing countries.

But in the United States, where there were two ART trials, both trials gave all HIV-positive patients access to anti-retroviral drugs, and no one received a placebo.

An editorial published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine argued that "most of these trials are unethical and will lead to hundreds of preventable HIV infections in infants." [1]

[1] Peter Lurie and Sidney M. Wolfe, 1997. "Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries." The New England Journal of Medicine 337(12):853-856. See also Marcia Angell, 1997, "The ethics of clinical research in the Third World," The New England Journal of Medicine 337(12):847-849.

Picture of a common rash encountered on HIV-positive children at a hospital in Jos, Nigeria.Photo by Mike Blyth. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Picture of a common rash encountered on HIV-positive children at a hospital in Jos, Nigeria.Photo by Mike Blyth. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Lurie and Wolfe

As Lurie and Wolfe pointed out in the New England Journal of Medicine

"Some officials and researchers have defended the use of placebo-controlled studies in developing countries by arguing that the subjects are treated at least according to the standard of care in these countries, which consists of unproven regimens or no treatment at all. This assertion reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the concept of the standard of care. In developing countries, the standard of care (in this case, not providing zidovudine to HIV-positive pregnant women) is not based on a consideration of alternative treatments or previous clinical data, but is instead an economically determined policy of governments that cannot afford the prices set by drug companies...

Acceptance of a standard of care that does not conform to the standard in the sponsoring country results in a double standard in research. Such a double standard, which permits research designs that are unacceptable in the sponsoring country, creates an incentive to use as research subjects those with the least access to health care." [1]

[1] Peter Lurie and Sidney M. Wolfe, 1997. "Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries." The New England Journal of Medicine 337(12):853-856.

Zidovudine, one of the antiretroviral therapy drugs used to treat mother-to-child transmission of HIV, but which was not provided to ART trial participants in Africa. Photo by Mike Blyth. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Zidovudine, one of the antiretroviral therapy drugs used to treat mother-to-child transmission of HIV, but which was not provided to ART trial participants in Africa. Photo by Mike Blyth. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Controversy Over Art Trials in Africa (continued)

While the issues involved are specific to biomedical research, no researchers should use a different standard of research ethics in other countries or amongst other populations than they would use amongst their own people.

In other words, if researchers can get away with different ethical standards when they do research in poor countries than they could get away with in their own wealthier countries, then there is a clear incentive to use poor people as their "guinea pigs." This violates the Helsinki declaration which says that no population should disproportionately bear the risks, or reap the benefits, of research.

It is reminiscent of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which poor African Americans were studied and not given any treatment for syphilis, while at the very same time elsewhere in the same state, others were given antibiotics to cure their syphilis. In the ART trial controversies, we see that certain parts of the world have been identified as cheap places to do research, but the same standards of care are not applied.

Other Research Ethics Protocols

Other protocols developed to guide ethical research include:

- The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) / World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines http://www.cioms.ch/frame_guidelines_nov_2002.htm

- The European Union's EU Clinical Trials Directive http://www.eortc.be/Services/Doc/clinical-EU-directive-04-April-01.pdf

- The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in the United States (its guidelines are called the Belmont Report) http://www.familyhm.org/Belmont%20Report.pdf

In Australia we follow:

- Australia's National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018

- Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-code-responsible-conduct-research-2018

The Code guides institutions and researchers in responsible research practices and promotes research integrity. The Code also shows how to manage breaches of the Code or misconduct, as well as how to manage and publish research data.

For eviDent projects, which are conducted under the auspices of the University of Melbourne, we are also bound by:

- The University of Melbourne's Code of Conduct for Research (Regulation 17.1.R8) https://gradresearch.unimelb.edu.au/roles-and-responsibilities/responsible-research

III. Basic Tenets of Ethical Research Practice

Introduction

This section reviews the basic tenets of ethical research practice. It is based on the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research.

According to the Australian National Statement, the relationship between researchers and research participants is one based on trust, mutual responsibility, and equality.

Ethical research is grounded in the values of:

1. beneficence

2. research merit and integrity

3. justice

4. respect for human beings

Photo by wallyg ("Respect"). Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Photo by wallyg ("Respect"). Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Beneficence

Beneficence: Maximize benefit, Minimize risks

The researcher must avoid risks or reduce them as much as possible. The researcher's priority should be the welfare of the participants in the research context.

Researchers, ethics committees, and research participants must make a calculation of the risks involved in participating in the research weighed against the potential benefits and knowledge to be gained. Any risk of harm or discomfort - or even inconvenience! - must be outweighed by the benefits to be gained by the research.

It is the responsibility of the researcher to ensure that benefits to research participants are optimal while the risks are reduced to a minimum.

Reference: Australian National Statement p.13-18.

Research Merit and Integrity

The involvement of human participants in research that has no merit cannot be ethically justifiable. Nor can research with researchers who have no integrity.

From the very beginning of any project, the development and consideration of proposals should be carefully considered with respect to the principles of conduct throughout the research, the accountability of the researchers, and the potential benefits of the project.

The researchers must plan a good investigative design informed by a commitment to research of the highest quality. The researchers must anticipate likely difficulties and address how these might be solved prior to the commencement of the project.

Any sources of funding, research sponsors, conflicts of interest or partiality must be explicit.

Reference: Australian National Statement p.12.

Anthropologist Pal Nyiri conducting fieldwork in China. Photo courtesy Pal Nyiri, all rights reserved.

Anthropologist Pal Nyiri conducting fieldwork in China. Photo courtesy Pal Nyiri, all rights reserved.

Justice

Researchers should make every effort to ensure a fair distribution of risks and benefits and that there is fair access to the benefits of the research.

- No one group (such as the poor, mentally disabled, those in developing countries, etc.) should disproportionately bear the risks of research.

- No one group (e.g. the researchers, people in wealthy countries) should reap all the rewards and benefits of research (in the form of publications, patents, knowledge, etc).

- Researchers must provide special protection for vulnerable groups.

- Justice does not permit using vulnerable groups - such as low-resource persons - as research participants for the exclusive benefit of more privileged groups.

- Recruitment and selection of participants must be done in a fair and equal manner.

- Research participants must be informed about the results of the research.

Reference: Australian National Statement p.12

Respect

"Respect for human beings is recognition of their intrinsic value." [1]

- Respect means recognising the value of human autonomy - the capacity to make one's own decisions.

- Respect ensures that dignity is valued.

- Every participant has the right to informed consent.

- Each person has the right and capacity to make her or his own decisions.

- Individuals should be empowered to make free decisions about participating in research.

The confidentiality of information supplied by research participants and the anonymity of respondents must be respected.

Yet respect is not just about individuals. No individual exists alone. People live in social groups and these groups may have their own particular customs, traditions, cultural heritage, and sensitivities, which must also be respected.

Respect must be accounted for at all stages of a project, i.e. in the planning, development, implementation, analysis, publication and presentation of data.

Any research project can develop in ways that raise unforeseen ethical complications. In particular, the developing nature of research agendas conducted over a long period of time may pose challenges to ensuring that the ongoing rights and dignity of the participant(s) are respected and protected.

[1] Australian National Statement p 13

hoto by Desirée Delgado's Delgado, copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

hoto by Desirée Delgado's Delgado, copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Special Protections for Vulnerable Communities

Children are a vulnerable community and require special protections when conducting research.

Respect "involves providing for the protection of those with diminished or no autonomy, as well as empowering them where possible and protecting and helping people wherever it would be wrong not to do so." [1]

Vulnerable groups may need particular protection from the risks of research participation. Such vulnerable groups include:

- those who lack capacity for informed consent

- those who are subordinate members of a hierarchical group

Dealing with vulnerable communities requires particular sensitivity. Sometimes community representatives can help researchers recognize the unique decision-making processes of individuals and communities and suggest the best ways to empower participants to make voluntary decisions. Doing research with vulnerable communities requires particular care in research design which will be carefully studied by Human Research Ethics Committees.

Some examples of vulnerable communities include prisoners, children, and the mentally disabled.

[1] Australian National Statement p.11. Also see the Australian National Statement, chapter 4 (p.51-76) to review ethical considerations specific to research participants, including vulnerable groups

Photo taken by a member of the Clinical Trial Group at Melbourne Dental School, The University of Melbourne

Photo taken by a member of the Clinical Trial Group at Melbourne Dental School, The University of Melbourne

Ethics Oversight Committees

To ensure ethical conduct in human research, research projects that carry more than low risk to research participants must be independently reviewed before research can begin. The review process takes place through an independent panel of people from diverse backgrounds. In Australia we have Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) that are responsible for the review process. There are particular rules about the composition of these HRECs. They should consist of:

- at least 2 lay people, a man and a woman, who are not themselves researchers and have no affiliation to the research institution;

- at least 1 person with experience in counselling or treatment of people;

- at least 1 person who performs pastoral care in the community, e.g. an Aboriginal elder or minister of religion;

- a lawyer;

- at least 2 researchers.

There must be at least 8 people on an HREC; they should be equally men and women, as far as possible, and at least a third of the members should be external to the institution that the HREC reviews research for.

Reference: See the National Statement p.79-82 for the rules about establishment, composition, and procedures of HRECs

Photo by Richard Rutter. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Photo by Richard Rutter. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

IV. Ethics Controversies: Case Studies

Introduction

In this section we will review 3 case studies from oral health clinical research together with a social science research case study.

Let’s start with a bit of background about clinical research involving humans.

Clinical research can be divided into 2 main types [1]:

- Observational

- Interventional

In observational research the subjects are observed and then compared. Issues in this kind of research are usually related to confidentiality and privacy. A dental example might be reviewing the records of patients who have had their wisdom teeth removed and determining the risk factors for post-operative infection.

In an interventional (or experimental) study, researchers apply a particular intervention (drug, surgery, restoration type) to the subjects and monitor the outcomes. The intervention group may be compared to a control group (e.g. other interventions or sometimes a placebo). The classic example of this type of research is the clinical trial. Issues for this kind of research often focus on informed consent and minimizing harm.

The following case studies are a mix of both observational and interventional research.

[1]. Ethics and law for the health professions. 2nd ed. Ian Kerridge, Michael Lowe, John McPhee. The Federation Press 2005.

Case Study 1: The Vipeholm Caries Study

Probably the most ethically controversial dental research took place at the Vipeholm Hospital in Lund, Sweden between 1945 and 1954 [1].

The Vipeholm Hospital was described as an institute for the “mentally deficient” receiving patients from all parts of Sweden. The main psychiatric conditions described were “idiocy” and “imbecility”. Most patients spent their whole lives there.

The study was started before the introduction of the Nuremberg Code in 1947, but the study continued for 7 years after the Code’s introduction.

[1] The Vipeholm caries study. Gustafsson BE, Quensel C-E, Lanker LS, Lundqvist C, Grahnen H, Bonow BE, Krasse B. 1954 Acta Odontol Scand. Vol 11, Issue 3-4, 232-264

This image was taken in 1908. Photographer unknown.

This image was taken in 1908. Photographer unknown.

The aim of the study was to determine the relationship between carbohydrate intake and dental caries (tooth decay) with the subjects in some groups fed caramels and toffees between meals, whilst other groups received extra carbohydrates at mealtimes. The study was performed under the direction of the Swedish Medical Board and was funded by the government, research funds and the chocolate and sweet manufacturers.

The results of the study were:

- all groups showed a slow but definite increase in bodyweight

- DMF (i.e. the number of decayed, missing and filled teeth) increased over the course of the study with the biggest increases in those groups consuming additional carbohydrates between meals.

- these increases stopped when the diet reverted to the pre-study diet.

The study also reported that prior to 1950 the majority of patients received no dental care (only 5.6% of existing cavities had been filled, and some extractions performed).

By the end of the study, the number of unfilled cavities had increased from 11,238 to 13,363

The study was conducted entirely without the consent of patients or their carers/families. Ethical issues were not discussed at staff meetings or mentioned in the original study paper, with the dentists involved reported as not seeing any ethical problems with the study itself.

After an initial release of some study results in 1952, some study funds were withdrawn (sugar manufacturer). Continuation of the studies was now dependent on government funding. However, in 1954 a bill was introduced into the Swedish parliament suggesting that new grants for the project should be refused and this was followed by the government not allowing the patients at Vipeholm to be used as research subjects from July 1955 onwards.

One of the participating dentists (Bo Krasse) still argues that the study is ethically defendable [1]. Indeed, the study had some very positive outcomes, including:

- a desirable objective

- meticulous, credible results

- providing information regarding caries risk and frequent ingestion of sugar allowing the introduction of public health messages.

- stimulating research on sugar-substitutes.

[1] The Vipeholm dental caries study: Recollections and reflections 50 years later. Bo Krasse. J Dent Res 80(9): 1785-1788, 2001.

Question?

Which basic tenets of ethical research practice do you think have been violated in this study?

Answer: All of them.

- Beneficence: benefits to research participants should be optimal, whilst risks should be reduced to a minimum. Participants had an increased rate of tooth decay and although it has been suggested that inmates received fillings, the study report does not indicate this.

- Justice: no one group should disproportionately bear the risks of research (e.g. mentally disabled).

- Respect: every participant has the right to informed consent.

- Vulnerable groups: as a vulnerable group, the mentally disabled residents at the Vipeholm Hospital were subordinate members of a hierarchical group.

Useful reading for those who want to know more about the events at Vipeholm:

Voices from Vipeholm, eds. Cecilia Nilsson and Carl-Ola Holmér, Foundation Medical history museums in Lund and Helsingborg. 1998

Case Study 2: Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis at Metropolitan Hospital New York City

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) is a painful acute infection of the gums accompanied by necrosis, ulceration, bleeding, malodour and possible systemic manifestations. It is now accepted that the micro-organisms present in NUG are also found in individuals without the disease and that an impaired host response is needed for the disease to occur. However, it was originally thought that NUG was an infectious disease.

Between 1937 and 1941 a survey [1] of all children admitted to the Metropolitan Hospital, New York City was performed. The aim of the survey was to determine the prevalence of NUG, possible aetiological factors and to compare the methods of treatment. One further aim was to determine “ease of communicability”.

To assess “ease of communicability” direct transmission of infectious micro-organisms from children with the disease to children without the disease was attempted; when attempts to infect children by placing the infectious material directly onto healthy gums and throats failed, additional cases were attempted. In these cases, the gums, pharynx and tonsils were first abraded before direct transmission.

In all cases none of the children developed the disease.

In the study report, no mention was made of consent being sought from either the children or their parents.

Question?

Which basic tenets of ethical research practice do you think have been violated in this study?

Answer:

- Beneficence: benefits to research participants should be optimal, whilst risks should be reduced to a minimum. Participants were at risk of developing a painful, debilitating disease.

- Justice: no one group should disproportionately bear the risks of research (e.g. children).

- Respect: every participant has the right to informed consent.

- Vulnerable groups: the children and their families were in a dependant relationship and as such were a vulnerable group. In these situations, potential participants must be given assurances that their refusal/agreement to participate in research will in no way affect their on-going medical treatment.

[1] Schwartzman, J., and Grossman, L.: Vincent’s ulceromembranous gingivostomatitis. Arc Pediatr 58: 515, 1941

Photo by A/Prof Ivan Darby, The University of Melbourne.

Photo by A/Prof Ivan Darby, The University of Melbourne.

Case study 3: Scientific fraud - Jon Sudbø

Australia’s National Statement states that unless proposed research has merit, and the researchers who are to carry out the research have integrity, the involvement of human participants in the research cannot be ethically justifiable. Researchers are required by the Statement and the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research to follow recognised principles of research conduct and to conduct research honestly.

Although scientific fraud may not always impact directly on research participants, the ethical “fall out” from such fraud can be far-reaching.

Consider the admission of fraud by the Norwegian oral cancer researcher Jon Sudbø.

Sudbø (a dentist and formerly a consultant oncologist and researcher) had published a report of a study suggesting that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. ibuprofen) reduced the risk of oral cancer in smokers. The report appeared in the Lancet in October 2005 [1].

Another researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health noticed that the data set that had reportedly been used to draw data from was not open at the time of the study and raised the alarm.

Sudbø has since admitted to fabricating the data for 900 patients in the study report and using fictional data in at least two other papers. Of the 38 articles published by him since 1993, 15 have been condemned as fraudulent by the independent Committee of Inquiry established to investigate the scandal.

Sudbø’s findings had been used by other researchers around the world to inform cancer treatments and other research studies. The Committee of Inquiry was unable to rule out any negative impacts on cancer patients. Additionally, these fraudulent studies diverted significant resources from other, legitimate research.

[1] Jon Sudbø, J.J. Lee, S.M. Lippman, J. Mork, S.Sagen, N. Flatner, A. Ristimaki, A. Sudbø, L. Mao, X. Zhou, W. Kildal, J.F. Evensen, A. Reith, A.J. Dannenberg (October 2005). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of oral cancer: a nested case control study. The Lancet 366 (9494):1359-1366. R. Horton (February 2006). Retraction – Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of oral cancer: a nested case control study. The Lancet 367 (9508): 382

Image: Dr Jon Sudbø (source Norwegian Radium Hospital, Oslo)

Image: Dr Jon Sudbø (source Norwegian Radium Hospital, Oslo)

Case Study 4: Gang Leader for a Day

Although this case study is social-science research based, there are aspects which may relate to observational research in the oral health area especially with regard to confidentiality and becoming aware of criminal activity through research.

When Sudhir Venkatesh was a first-year PhD student in sociology, he decided to do research on the urban poor in government-subsidized housing projects not far from the University of Chicago. So one day he went into one of the housing project's high rise buildings with a clipboard and a questionnaire on poverty and started climbing the stairs. When he got to the fifth floor, he was stopped by the local gang that was hanging out in the stairwell. They held him hostage overnight in the urine-soaked stairwell.

At first they thought he might be part of a rival gang. When he explained about his research project, they were sceptical and decided to hold him until their boss arrived. Sometime in the early hours of the morning, the gang leader, J.T. showed up, and they started talking about Venkatesh's research. By the time the sun came up, J.T. decided to let Venkatesh go. Surprisingly, he also invited him to come back and "hang out" to get to know the lives of the urban poor better than he ever could from a multiple-choice survey.

That was the beginning of nearly a decade of ethnographic research with a crack-dealing gang in the Chicago housing projects. Venkatesh, now a sociology professor at Columbia University in New York, wrote about his experience in a book called "Gang Leader for a Day."

Photo copyright Ry Pepper.

Photo copyright Ry Pepper.

That experience offered Venkatesh incredible insights into the economics and social rules of an urban U.S. gang, a subculture that very few social scientists have ever had access to. But it also pointed to the ethically troubling aspects of his research. Venkatesh was regularly exposed to the gang's criminal activities, including not only the day-to-day aspects of selling crack cocaine, but even, occasionally, the planning of drive-by shootings.

When social scientists uncover crime through their research

This put him in terribly risky legal situations (and at the time, he did not even realize just how risky they were). Different countries have different laws about the reporting obligations of those who observe criminal activity, but in many places, citizens have an obligation to report a serious crime being planned. Also, unlike lawyers, doctors, dentists and clergy members (and, in some U.S. states, journalists), there is no researcher-client confidentiality law protecting social science researchers. In other words, social scientists usually are not legally protected if they wish to protect their informants by refusing to cooperate with the police who are investigating criminal activity.

Venkatesh was a graduate student and he hadn't been properly trained in these aspects of research ethics (he was doing his research at a time when social science researchers usually did not have to get ethics approval before doing research). When his professors found out more about what kind of things he was encountering during his research, they warned him that if he didn't report a drive-by shooting that he knew was being planned and someone died in that shooting, he could be charged as an accessory to murder.

Copyright Niccolò Bazzani (juliusfrumble)

Copyright Niccolò Bazzani (juliusfrumble)

No confidentiality for research participants when crime occurs

Further, the fact that there was no law protecting social scientists from having to testify if they witnessed criminal activity meant that if the police questioned Venkatesh, he might be forced to either turn over his notebooks with all his field notes or else go to jail himself. If he was accused of participating in a crime, his records could be subpoenaed. In other words, there was no way he could assure his research participants of confidentiality.

This is a serious consideration in social science research, even when the research isn't as dramatic as Venkatesh's research on crack-selling gangs who planned drive-by shootings. Sometimes a researcher isn't planning on conducting research on criminal activity, but it comes up in conversations on other subjects. For example, say you are doing research on cigarette smoking, but as you talk to the smokers, they start telling you about the illicit drugs they use.

What do you do?

The answer is not simple. In the example above, for example, it can depend on whether the drug use occurred in the past or in the present, whether it is personal drug use or if it also involves dealing drugs, and also whether minors are involved.

For these reasons, it is impossible to provide blanket guidelines. Probably the first thing you should do is stop the research and get the advice of your research supervisor, who may in turn need to consult with a legal expert and/or your local ethics supervisory board.

What do you do when your research uncovers illegal activity?

If you are doing research and you discover illegal activity, you should consult someone who can advise you on how to balance your obligation to provide confidentiality to your research participants with your reporting responsibilities under the law.

You can imagine this as a continuum. At one end is a situation where you may have a legal or moral obligation to provide information to the police in order to "prevent or lessen a serious and imminent threat to the life or health of the individual concerned or another person." [1] (Hearing people plan a drive-by shooting definitely falls in this category.) In Australia, certain kinds of crime have mandatory reporting requirements, including crimes against minors and persons who are mentally ill or intellectually impaired.

At the other end of the continuum, if you uncover a minor crime that has no external victim (such as personal drug use), then your chief obligation is to protect the confidentiality of your informant. This means thinking carefully about whether your informants can be identified from your research field notes. Remember that your research records may be subject to subpoena, freedom of information request or mandated reporting. Your participants should be advised of this before consenting. If the research involves the investigation of illegal behaviour, it is often recommended that the identities of the participants remain anonymous in all research records.

For more information on Professor Sudhir Venkatesh's research: http://sudhirvenkatesh.org or his Columbia University faculty page http://www.sociology.columbia.edu/fac-bios/venkatesh/faculty.html

Sudhir Venkatesh discusses these ethical conundrums in his riveting book, 'Gang Leader for a Day'

That book is written for a more popular audience, but Professor Venkatesh has also published a number of academic articles and books on his research, including:

- American Project: The Rise and Fall of a Modern Ghetto. Harvard University Press, 2000

- Off the Books: The Underground Economy of the Urban Poor. Harvard University Press, 2006

- Venkatesh's work has also been featured in Freakonomics by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner, in a chapter he co-wrote with Levitt called "Why Do Drug Dealers Still Live With Their Moms?".

He is a guest blogger for the NY Times "Freakonomics" blog. http://freakonomics.blogs.nytimes.com/tag/sudhir-venkatesh/

[1] National Health and Medical Research Council, http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/e72syn.htm

Cartoon by Paul Mason. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Cartoon by Paul Mason. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

V. Research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

Introduction

From the outset, it should be said that Indigenous Australians are not 'a unitary people, or a nation with a unitary culture or way of life: "Australian Aboriginal" is an umbrella term covering very deep and wide differences.' [1]

This means that Australian Indigenous people live in many different ways in many different places. More than 70%, for example, live in urban contexts, but the ways in which different groups and individuals live in cities varies according to where the people concerned originally came from, their relationships with each other, their relationships with the wider Australian society, and how they relate to the city as 'home'.

For example, some Indigenous people living in the city live as suburban neighbours, participating in everyday life in ways which are indistinguishable from any other Australian citizen. Others, on the other hand, live as fringe dwellers, alienated and marginalised from the benefits and responsibilities of other Australians. Still others participate in most aspects of Australian social life, but also engage in a diverse range of specifically Indigenous cultural practices including ceremonies, creating Indigenous art works, and performing dances and songs which represent their Aboriginal identity.

What kinds of problems result from thinking of Indigenous Australians as one homogeneous group?

Some examples:

- Indigenous identities are reduced into a category that is easy for non-Indigenous people to understand, but which reduces the richness and diversity of Indigenous cultures.

- Due to a history of thinking which 'primitivisms' Indigenous peoples, many Indigenous Australians struggle with asserting their identities as 'authentic.' For example, if people who have seen Baz Lurhmann's movie Australia imagine Indigenous people to just be magical, mud-smeared medicine men who communicate telepathically and wear loin cloths, then Indigenous Australians who live in the city and have a regular nine-to-five job may be seen as 'inauthentic.' But of course, there are countless ways to be authentically Indigenous!

The history of believing Indigenous Australians to be radically different to (and more primitive than) Eurpoeans began in the nineteenth century. Researchers working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities should be aware of the damaging legacy of research of previous generations to help avoid future mistakes and to understand the anxieties and reservations of some of the communities.

Reference: Jeffery Sissons, First peoples: Indigenous cultures and their futures. London. Reaktion Books.

[1] Jeffery Sissons, First peoples: Indigenous cultures and their futures. London. Reaktion Books

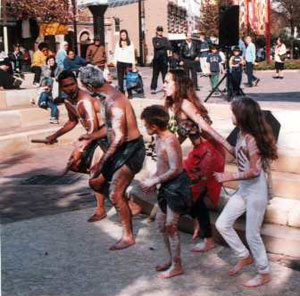

Urban Aboriginal Australians dancing in Sydney. Copyright 2003 Kristina Everett, all rights reserved.

Urban Aboriginal Australians dancing in Sydney. Copyright 2003 Kristina Everett, all rights reserved.

The Negative Legacy of Research: The Stolen Generation

Here is an example of how early anthropological research on Australian Indigenous groups led to devastating results for Indigenous communities.

Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer (1860-1929), an early Australian scientist and anthropologist, was a proponent of a theory of racial hierarchy which placed Australian Aborigines into a category that "represent the most backward race extant and, in many respects, reveal to us the conditions under which the early ancestors of the present human races evolved." [1]

As an influential academic, Baldwin Spencer's writings were wide-reaching and had an enormous impact on public perceptions of Indigenous culture. His writings were based on fieldwork, but imbued with the misunderstandings of his generation. These included believing in Darwinian hierarchies and the belief that Indignity is a genetic condition that exists in 'the blood'. Such eugenicist beliefs are still current and have resulted in some of the greatest atrocities in human history including the Holocaust, Pol Pot and Rwanda.

Another belief of this era which is still current in some quarters is that identity is genetic, so "mixed race" Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may inherit some of the "advantages" of their European parent and may be redeemable as more "superior" human beings to their Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander parent. These children were referred to with what is now considered to be the demeaning term "half-caste."

Bearing these beliefs, Spencer became "Chief Protector of Aborigines" in the Northern Territory from 1911-1913, which made him a strong advocate of the forced removal policies that led to what is known today as the "stolen generation":

"No half-caste children should be allowed to remain in any native camp but they should all be withdrawn and placed on stations. So far as practicable, this plan is now being adopted. In some cases, when the child is very young, it must of necessity be accompanied by its mother, but in other cases, even though it may seem cruel to separate the mother and child, it is better to do so, when the mother is living, as is usually the case, in a native camp." [2]

The impact on Indigenous families and children was devastating. Can you imagine how a parent feels to have his or her children forcibly taken from them? Many of the children who became wards of the state experienced abuse, including physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. According to Reconciliation Australia,

"The Bringing Them Home report found that many children were removed solely on the basis of skin colour. Because of this, siblings from the one family who were considered to be of lighter skin colour would be removed when others were left.

"The suggestion those stolen generations children were better off is untrue on any reasonable assessment of the cases where they were placed in situations of deprivation, neglect and abuse. People who were removed gave evidence to the Inquiry of their mistreatment under State care - this ranged from inadequate food and clothing, to physical, sexual and psychological abuse.

"Almost a quarter of witnesses to the Inquiry who were fostered or adopted reported being physically abused. One in five reported being sexually abused." [1]

The underlying intellectual foundation justifying the policies of forcibly removing Indigenous children from their communities was the 'scientific' racism of social scientists. Think back to the legacy of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment on African Americans. Similarly, is it any wonder that many Aboriginal communities are sceptical or distrustful about the motivations and outcomes of social science research in their communities?

[1] Spencer quoted in Warwick Anderson, The Cultivation of Whiteness: Science, Health and Racial Destiny in Australia (New York: Basic Books, 2003, p201.

[2] Walter Baldwin Spencer, "Preliminary Report on the Aborigines of the Northern Territory" as quoted in National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families (Australia), Ronald Darling Wilson, and Australia. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Bringing Them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families (Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1997), p 133.

[3] http://www.reconcile.org.au/getsmart/pages/sorry/sorry--faq.php, retrieved 23 December 2008

Picture of Baldwin Spencer Building at The University of Melbourne.Photo by flipsockgrrl (sneedleflipsock.com), all rights reserved.

Picture of Baldwin Spencer Building at The University of Melbourne.Photo by flipsockgrrl (sneedleflipsock.com), all rights reserved.

Guidelines for Ethical Research

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies released a set of Guidelines for Ethical Research in Indigenous Studies in May 2000. They establish the following 11 principles of ethical research:

A. Consultation, negotiation and mutual understanding

- Consultation, negotiation and free and informed consent are the foundations for research with or about Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- The responsibility for consultation and negotiation is ongoing.

- Consultation and negotiation should achieve mutual understanding about the proposed research.

B. Respect, recognition and involvement

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and processes must be respected.

- There must be recognition of the diversity and uniqueness of peoples as well as of individuals.

- The intellectual and cultural property rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples must be respected and preserved.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers, individuals and communities should be involved in research as collaborators.

C. Benefits, outcomes and agreement

- The use of, and access to, research results should be agreed.

- A researched community should benefit from, and not be disadvantaged by, the research project.

- The negotiation of outcomes should include results specific to the needs of the researched community.

- Negotiation should result in a formal agreement for the conduct of a research project, based on good faith and free and informed consent.

Source: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2000. Guidelines for Ethical Research in Indigenous Studies, p.3-5. Available online at http://www.aiatsis.gov.au/research/docs/ethics.pdf retrieved 11 March 2010. Explanation and guidelines for implementation are found in the original document.

Aboriginal flag. Photo by Clive Stacey. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Aboriginal flag. Photo by Clive Stacey. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Summary of the Principles of Ethical Research Developed by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are diverse and unique. They have different languages, cultures, histories, and perspectives. These differences must be recognised, acknowledged and respected. It is also important to understand value and respect the diversity of individuals and groups within these communities. Research projects with or about Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples should incorporate their perspectives and be planned with continuing opportunities for consideration by the community. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander researchers, individuals and/or communities should be involved and considered as research collaborators. The researchers must accept a degree of community input into and control of the research process.

Research should not be researcher biased. The act of consultation and negotiation is not simply a matter of courtesy but an opportunity for groups to be properly, freely and fully informed. It must acknowledge and respect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and processes, ideas, cultural expressions and cultural materials. The researched community should not be disadvantaged by the research project. There must be mutual understanding that participants have the right to withdraw from the project at any time.

Researchers have an obligation to provide free and informed consent as well as an obligation to give something back to the community. Research results should be shared in a form that is useful and accessible. Recognition for the contribution of communities and individuals should be acknowledged appropriately. This recognition should also be discussed with potential contributors prior to the commencement of the project.

The six values that lie at the heart of the "Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research" endorsed by Council on 5 June 2003 are:

Reciprocity, Respect, Equality, Survival and Protection, Responsibility, and Spirit and Integrity

Reciprocity

Principles of research conduct should always be founded on respect for peoples' inherent right to self-determination, and to control and maintain their culture and heritage. Research with and about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples must essentially be found on a process of meaningful engagement and reciprocity.[1]

Researchers demonstrate reciprocity through the sincere intention to contribute to the advancement of the health and wellbeing of participants and communities participating in the research. Research should respond to existing or emerging needs articulated by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. There should be clear links between the research proposals and the priorities of community, regional, jurisdictional and /or international indigenous health. Prior to the consensual approval and commencement of a research project, there should be a clear and truthful discussion of the nature of the research proposal and potential benefits for the participants. The researchers must be willing to modify research in accordance with participating community values and aspirations. Wherever possible, collaborative partners in a research project should seek to enhance the capacity of communities to draw benefit beyond the project.

Respect

A functioning and moral society depends upon the respect of human dignity and individual worth. Respect is at the core of all aspects of any research process. People have the right to different values, norms and aspirations. Respectful research relationships acknowledge and affirm these rights.

Every effort should be made to minimise the possibility of overlooking differences. Ethical researchers consider and recognise the right to difference, the contributions of participating groups and individuals and the consequences of research at all stages of the process.

There is no greater priority of a researcher than the feedback of findings to a community in an appropriate and understandable way. Researchers need to develop sensitivity to social and cultural processes and understand how their research engages with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' values, knowledge and experience.

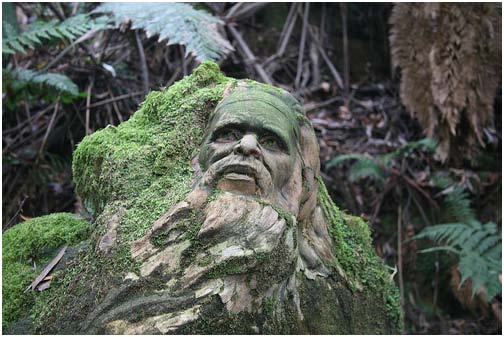

William Ricketts Sanctuary, Mt Dandenong. Photo: Julie Strahan/jsarcadia photography. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

William Ricketts Sanctuary, Mt Dandenong. Photo: Julie Strahan/jsarcadia photography. Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Equality

Equality is embodied by a commitment to distributive fairness and justice. It is a feature of the fundamental dignity of humanity.

All researchers must recognise and acknowledge the equal value of people and the right to be different. The history of marginalisation of Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islander cultures has created inequalities and led to discrimination, stereotyping and disregard. Researchers should seek to advance the elimination of such inequalities. They must value the systems of knowledge and wisdom as well as how this knowledge and wisdom is imbricate in the collective memory and shared experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Research agreements must have the strength necessary to sustain equality. Researchers can then demonstrate equality by helping the participating communities understand the proposed research and gain satisfaction from the equal distribution of any benefits.

Survival and Protection

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples place particular importance on collective identity. They act to protect the distinctiveness of their cultures and identity from erosion by colonisation and marginalisation. Past research has given the perception of research as an exploitative exercise. Current researchers have to make efforts to demonstrate - through ethical negotiation, conduct and dissemination of research - that they are trustworthy.

Researchers should have respect for social cohesion, a commitment to cultural distinctiveness, and understand the importance of solidarity to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Research partners need to assess if the research project contributes to or erodes the social and cultural bonds among and between the participating communities. Measures to safeguard against the contribution to discrimination or derision should be set in place.

Urban Aboriginal boys attending a culture day in Penrith. Copyright 2003 Kristina Everett, all rights reserved.

Urban Aboriginal boys attending a culture day in Penrith. Copyright 2003 Kristina Everett, all rights reserved.

Responsibility

"Ethical research occurs when harmony between the sets of responsibilities is established, participants are protected, trust is maintained and accountability is clear." [1]

Core responsibilities recognised by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples:

- responsibilities to country,

- to kinship bonds,

- caring for others and

- the maintenance of harmony and balance within and between the physical and spiritual realms

Research partners have a responsibility to do no harm. Researchers have an accountability to individuals, families and communities. They demonstrate responsibility through the transparent exchange of ideas and the open negotiation of purpose, methodology and conduct, dissemination of results and potential outcomes/benefits of research.

Researchers have an obligation to provide timely and relevant feedback to communities. This feedback should address the concerns, values and expectations expressed by the research participants and communities.

Publication arrangements of the research results should be mutually agreed upon. The demand on partners and the potential implications arising from the research and subsequent publication should be made clear.

Photo by Benjamin Whitehouse. Creative Commons

Photo by Benjamin Whitehouse. Creative Commons

Conclusions

There are three key points to take away from this review of the history of research with Indigenous communities and the links with Australian government interventions.

First, the example of the long history of the removal of Indigenous children from their families due to the erroneous theorising of powerful whites explains why Indigenous communities remain deeply sceptical about research, even now that the scientific racism of previous generations has been rejected by researchers. As long as research is used to justify imposing "solutions" onto Indigenous communities without their consent, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians will continue to reject the entire Western research paradigm.

Second, what the various examples of the Stolen Generations demonstrate is that research in Australia is rooted in a history of colonial violence. While governments have said that these policies are for the good of Indigenous communities, they have typically been imposed without having any discussion with Indigenous communities about what would actually benefit them, and they have often been damaging to Indigenous families and communities.

And third, that researchers cannot assume that the 'things' - objects, knowledge, values and ideas - that Indigenous research participants reveal and/or expose in the research process are simply 'available' or 'out there' for anyone to own or keep.

Researchers working with Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander groups are advised to read the complete ethical guidelines to research with these communities:

Individuals planted "sorry hands" in the soil outside the Redfern Community Centre in inner-city Sydney and a crowd watched the screening of Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's formal apology to the Indigenous people of Australia.Photos by Sidat de Silva (sorry hands) and Keith Fauxtographix, Canberra (Kevin Rudd screening). Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Individuals planted "sorry hands" in the soil outside the Redfern Community Centre in inner-city Sydney and a crowd watched the screening of Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's formal apology to the Indigenous people of Australia.Photos by Sidat de Silva (sorry hands) and Keith Fauxtographix, Canberra (Kevin Rudd screening). Copyright Creative Commons, some rights reserved.

Conclusions: Reflections on an Imperfect History

It is important to understand that ethics in many research contexts are part of a particular colonial history. Current research ethics are a point on a continuum from a time when it was considered to be acceptable for European researchers to collect and distribute any information and/or objects they liked (including human bodies and body parts) in the name of scientific discovery. Things have changed, but they are not perfect. 'Decolonising methodologies' can only ever go part way in being truly 'decolonising' when power relationships in research are unequal as they very often are.

Institutional ethics guidelines are also only part of ethical research practice. The rules that are legislated by institutions for their researchers can never take account of the infinitely variable nature of research and research relationships. Often, the ethics rules demanded by institutions fall well short of the demands of personal relationships between researchers and their research participants.

An example of this occurred during anthropologist Kristina Everett's research with an urban Aboriginal community. The University Ethics Committee to which she was accountable demanded that she obtain a signed letter of consent from a research participant who had asked Everett to write her life history. Everett asked the woman, with whom Everett had enjoyed a long term, warm relationship, to sign the form a number of times, but the woman had resisted. When Everett finally confronted the issue with the woman she became very upset and argued that it was insulting that friends should need a contract to protect what the woman understood to be the interests of the university rather than her own interests. She claimed that she and Everett had been through enough personal trials over the years to trust each other and that a piece of paper would never be able to do what their relationship demanded.

Institutional ethics rules can also fall short of researcher's own moral responsibilities and commitments to a particular cause. Ultimately, researchers must make their own decisions about what is ethical in the context of the particular research situation, in dialogue with their research participants.

Urban Aboriginal person doing crafts. Photo copyright 2003 Kristina Everett, all rights reserved.

Urban Aboriginal person doing crafts. Photo copyright 2003 Kristina Everett, all rights reserved.

Final Thoughts

Ethics Are Contested: Where Do You Stand?

This ethics module offers a few concrete recommendations – like "do no harm" – but overall what it emphasises is that research ethics are contested, both within and across disciplines. Everyone may agree on fundamental principles like "do no harm," but there is significant debate about what constitutes "harm" and how to calculate the risk-benefit ratio. The case studies we have reviewed show that researchers have reached completely different conclusions about a range of issues, including what research collaboration should look like, how to give back to the community you research, whether deception in research can ever be ethical.

The historical and contemporary controversies reviewed, from the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment to Gang Leader for a Day, shows that there is no triumphant, linear progress towards ethical enlightenment. Despite the international spread of ethics regulatory regimes and surveillance, research ethics scandals and controversies are unfolding as we speak. This training program presents ethics as set of conflicts to negotiate, conundrums to consider, and a personal relationship that researchers develop with colleagues, informants, collaborators, mentors, and friends in their field site.

You may or may not agree with our treatment of particular issues, but either way, we hope that it is a useful resource for prompting debate and discussion about research ethics. The text and many of the photographs are licensed through a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike license, so they can be used to develop your own educational materials. We welcome feedback at .

Many thanks to Lisa Wynn for her help with modifying her original module; here are her acknowledgements:

This training module was funded by a Teaching and Learning Award from Macquarie University. Thanks to Provost Judyth Sachs for her support for this project, and to the Macquarie University Learning & Teaching Centre for their fabulous graphic design. A big shout out to all those who generously contributed photographs to illustrate the website, including Philip Zimbardo, Sudhir Venkatesh, Julienne Corboz, Anne Monchamp, Pál Nyíri, Jessie Zhang, Sarah Andrieu, Arman Abrahamyan, Jorge Cham, Pitzer College, Pomona College, Stanford University, the State Library of South Australia, the U.S. National Archives, the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Open Society Institute, the U.S. Department of Defence, and all the fabulous people who have licensed their Flickr photos with Creative Commons.